She runs across the street to the park and plays there alone, beneath the budding trees, while her mother stands on the corner and bites the tips of her fingers. The girl climbs into the swing and pendulums back and forth, pumping her legs, and watching her opens some valve a Werner's soul. This is life, he thinks, this is why we live, to play like this on a day when winter is finally releasing its grip. He waits for Neumann Two to come around the truck and say something crass, to spoil it, but he doesn't, and neither does Bernd, maybe they don't see her at all, maybe this one pure thing will escape their defilement, and the girl sings as she swings, a high song that Werner recognizes, a counting song that girls jumping rope in the alley behind Children's House used to sing. Eins, zwei, Polizei, drei, vier, Offizier, and how he would like to join her, push her higher and higher, sing funf, sechs, alte Hex, sieben, acht, gute Nacht! Then her mother calls something Werner cannot hear and takes the girl's hand. They pass around a corner, little velvet cape trailing behind, and are gone.

Uma Aventura Literária

O livro é uma coisa espantosa. É um objecto plano, feito a partir de uma árvore . É montado com um conjunto de partes planas e flexíveis (que ainda são chamadas de "folhas") onde estão impressos rabiscos de pigmento preto. Basta dar-lhe uma olhada e começámos a ouvir a voz de outra pessoa, talvez de alguém que já morreu há milhares de anos. O seu autor fala através dos milénios de forma clara e silenciosa, dentro da nossa cabeça, directamente para nós. A escrita é talvez a maior das invenções humanas, que junta pessoas, cidadãos de outras épocas, que nunca se conheceram. Os livros quebram as correntes do tempo e são a prova de que os humanos conseguem fazer magia. - Carl Sagan

segunda-feira, 28 de dezembro de 2015

domingo, 27 de dezembro de 2015

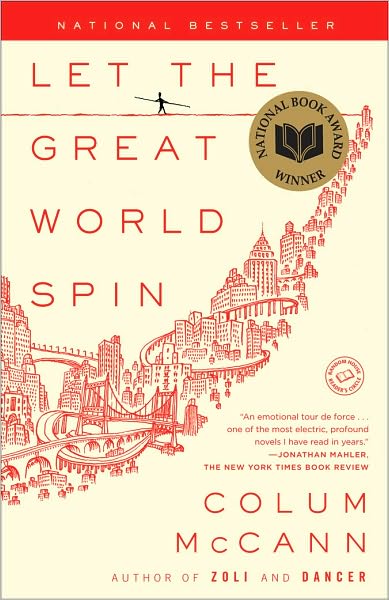

Deixa o Grande Mundo Girar - Colum McCann

O porteiro ligou-lhe e ela desceu as escadas a correr, saiu para a rua e pagou ao motorista de táxi. Olhou para baixo para os meus pés - uma pequena barreira de sangue tinha crescido na orla do calcanhar e a algibeira do meu vestido estava rasgada - e alguma coisa deu a volta dentro dela, alguma chave, o seu rosto enterneceu-se. Pronunciou o meu nome e, por um momento, senti-me incomodada. Rodeou-me com o braço e levou-me directamente para dentro do elevador e pelo corredor em direcção ao quarto. Os cortinados estavam corridos. Emanava dela um cheiro forte a cigarros, misturado com perfume fresco. - Aqui - disse ela, como se fosse o único lugar no mundo. Sentei-me sobre a roupa da cama limpa, sem uma ruga, enquanto ela punha um banho a correr. O esparrinhar da água. - Pobrezinha! - chamou ela. Havia no ar um odor a sais perfumados.

Vi o meu reflexo no espelho da cama. O rosto estava com aspecto bafurido e exausto. Ela estava a dizer alguma coisa, mas a sua voz foi envolvida pelo ruído da água.

O outro lado da cama estava amarrotado. Assim, ela tinha estado deitada, talvez a chorar. Tive vontade de me sentar em cima da sua marca, aumentando-a três vezes mais. A porta abriu-se lentamente. Claire estava a sorrir. - Vamos pôr-te em forma - disse ela. Veio até à beira da cama, pegou no meu cotovelo, conduziu-me à casa de banho, sentou-se num banco de madeira junto à banheira. Inclinou-se e experimentou a temperatura da água com o nó do dedo. Descalcei as meias. Pequenos pedaços de pele saíram dos meus pés. Sentei-me no extremo da banheira e passei as pernas para o outro lado. A água fez arder. Escorreu sangue dos meus pés. Como um pôr do sol a desvanecer-se, o brilho avermelhado a dispersar-se dentro de água.

Claire colocou uma toalha branca no meio do chão da casa de banho, aos meus pés. Deu-me alguns pensos rápidos, com o painel protector já tirado. Não pude deixar de pensar que ela tinha vontade de secar-me os pés com o seu cabelo.

- Eu estou bem, Claire - disse-lhe eu.

- Que é que te roubaram?

- Apenas a minha bolsa.

Senti-me invadida pelo receio: ela podia pensar que eu queria apenas o dinheiro que me havia oferecido para ficar, receber a minha recompensa, a minha bolsa de escrava.

- Não tinha dinheiro.

- De qualquer forma, vamos chamar a polícia.

- A polícia?

- Porque não?

- Claire...

Ela olhou para mim sem compreender, e depois um entendimento atravessou os seus olhos. As pessoas acham que conhecem o mistério de se viver dentro da nossa pele. Não conhecem. Não há ninguém que saiba a não ser a pessoa que acarreta com isso dentro de si.

- Queres saber o pior nisto? - disse eu.

- O que foi?

- Ela chamou-me gorda.

quarta-feira, 16 de setembro de 2015

Níveis de Alerta Europeus - John Cleese

Os ingleses sentem apreensão em relação aos recentes acontecimentos na Síria, o que os levou a aumentar o nível de segurança de "Indispostos" para "Incomodados". Em breve, os níveis de segurança podem voltar a aumentar para "Irritados" ou até "Um Pouco Zangados". Os ingleses já não estão "Um Pouco Zangados" desde o Blitz em 1940 quando o fornecimento de chá quase acabava. Os terroristas mudaram de categoria, passaram de "Chatos" para "Um Raio de um Transtorno". Os ingleses já não emitiam um aviso de "Um Raio de Transtorno" desde 1588 quando ameaçaram a Armada Espanhola.

Os escoceses aumentaram o seu nível de segurança de "Chateados" para "Vamos Dar Cabo desses Cabrões". Eles não têm mais níveis. É por isso que o exército britânico os coloca na frente da batalha há 300 anos.

Os governo francês anunciou ontem que aumentou o nível de alerta terrorista do país de "Fujam" para "Escondam-se". Os únicos níveis mais elevados do que estes na França são "Colaborem" e "Rendam-se". O aumento foi motivado por um incêndio que recentemente destruiu a fábrica de bandeiras brancas da França, o que paralisou por completo o exército do país.

A Itália aumentou o seu nível de alerta de "Gritar Alto e com Entusiasmo" para "Encenações Militares Elaboradas". Porém, ainda restam mais dois níveis de alerta: "Operações de Combate Ineficazes" e "Mudar de Lado".

Os alemães aumentaram o seu nível de alerta de "Arrogância com Desdém" para "Colocar o Uniforme e Cantar Canções de Marcha". Este país também possui mais dois níveis de alerta: "Invadir um Vizinho" e "Perder".

Já os belgas, estão todos de férias como é costume; a única coisa que os preocupa é a possibilidade de a NATO sair de Bruxelas.

Os espanhóis estão todos entusiasmados por finalmente poderem dar uso aos seus submarinos. Estas belas máquinas têm fundos em vidro para que a nova marinha espanhola consiga ver bem a velha marinha espanhola.

Quanto à Austrália, aumentou o seu nível de segurança de "Sem Stress" para "Isto Resolve-se, Meu". Ainda restam dois níveis de alerta: "Bolas! Acho que Vamos Ter de Cancelar a Churrascada Deste Fim-de-semana" e "A Churrascada está Cancelada". Até hoje, ainda nada levou o país a fazer uso deste último nível da escala.

Agora, deixo-vos com este pensamento para acabar: "A Grécia está em colapso, os iranianos estão a ficar agressivos e Roma está num caos. Bem-vindos de volta a 430 A.C.

quarta-feira, 26 de novembro de 2014

"A Relíquia" - Eça de Queirós

Corri ao quarto, a buscar essas doces «lembrancinhas» da Palestina. E ao regressar, sustentando pelas pontas um lenço repleto de devotas preciosidades, estaquei por trás do reposteiro ao sentir dentro o meu nome... Suave gozo! Era o inestimável Dr. Margaride que afiançava à titi com a sua tremenda autoridade:

- D. Patrocínio. eu não lho quis dizer diante dele... Mas isto agora é mais do que ter um sobrinho e ter um cavalheiro!

Isto é ter, de casa e pucarinho, um amigo íntimo de Nosso Senhor Jesus Cristo!

Tossi, entrei. Mas a Sr.ª D. Patrocínio ruminava um escrúpulo ciumento. Não lhe parecia delicado para Nosso Senhor (nem para ela) que se repartissem estas relíquias mínimas antes de lhe ser entregue a ela, como senhora e como tia, na capela, a grande relíquia...

- Porque saibam os meus amigos - anunciou ela com o seu chatíssimo peito impando de satisfação - que o meu Teodorico trouxe-me uma santa relíquia, com que eu me vou apegar nas minhas aflições, e que me vai curar dos meus males!

- Bravíssimo! - gritou o impetuoso Dr. Margaride. - Com quê, Teodorico, seguiu-se o meu conselho? Esgravataram-se esses sepulcros?... Bravíssimo! É de generoso romeiro!

- É de sobrinho, como já o não há no nosso Portugal! - acudiu o padre Pinheiro junto ao espelho, onde estava a língua saburrenta...

- É de filho, é de filho! - proclamava o Justino, alçado na ponta dos botins.

Então o Negrão, mostrando os dentes famintos, babujou esta coisa vilíssima:

- Resta saber, cavalheiros, de que relíquia se trata.

Tive sede, sede ardente do sangue daquele padre! Trespassei-o com dois olhares mais agudos e faiscantes do que espetos em brasa.

- Talvez Vossa Senhoria, se é um verdadeiro sacerdote, se atire de focinho para baixo rezar quando aparecer aquela maravilha!...

E voltei-me para a Sr.ª D. Patrocínio, com a impaciência de uma nobre alma ofendida que carece reparação:

- É já, titi! Vamos ao oratório! Quero que fique tudo aqui assombrado! Foi o que disse o meu amigo alemão: «Essa relíquia, ao destapar-se, é de ficar uma família inteira assombrada!...»

Deslumbrada, a titi ergueu-se de mãos postas. Eu corri a prover-me de um martelo. Quando voltei, o Dr. Margaride, grave, calçava as suas luvas pretas...E atrás da Sr.ª D. Patrocínio, cujos cetins faziam no sobrado um ruge-ruge de vestes de prelado, penetrámos no corredor onde o grande bico de gás silvava dentro do seu vidro fosco. Ao fundo, a Vicência e a cozinheira espreitavam com os seus rosários na mão.

O oratório resplandecia. As velhas salvas de prata, batidas pelas chamas das velas de cera, punham no fundo do altar um brilho branco de glória. Sobre a candidez das rendas lavadas, entre a neve fresca das camélias - as túnicas dos santos, azuis e vermelhas, com o seu lustre de seda, pareciam novas, especialmente talhadas nos guarda-roupas de Céu para aquela rara noite de festa... Por vezes o raio de uma auréola tremia, despendia um fulgor, como se na madeira das imagens corressem estremecimentos de júbilo. E na sua cruz de pau-preto, o Cristo, ríquissimo, maciço, todo de ouro, suando ouro, sangrando ouro, reluzia preciosamente.

- Tudo com muito gosto! Que divina cena! - murmurou o Dr. Margaride, delicado na sua paixão do grandioso.

(...)

Acordando do seu langor, trémula e pálida, mas com a gravidade de um pontífice, a titi tomou o embrulho, fez mesura aos santos, colocou-o sobre o altar: devotamente desatou o nó do mastro vermelho; depois, com o cuidado de quem teme magoar um corpo divino, foi desfazendo uma a uma as dobras do papel pardo... Uma brancura de linho apareceu... A titi segurou-a nas pontas dos dedos, repuxou-a bruscamente - e sobre a ara, por entre os santos, em cima das camélias, aos pés da cruz, espalhou-se, com laços e rendas, a camisa de dormir da Mary!

A camisa de dormir da Mary! Em todo o seu luxo, todo o seu impudor, enxovalhada pelos meus braços, com cada prega fedendo a pecado! A camisa de dormir da Mary!

quinta-feira, 7 de novembro de 2013

'Anansi Boys' - Neil Gaiman

"Spider was having a great day at the office. He almost never worked in offices. He almost never worked. Everything was new, everything was marvelous and strange, from the tiny lift that lurched him up to the fifth floor, to the warrenlike offices of the Grahame Coats Agency. He stared, fascinated, at the glass case in the lobby filled with dusty awards. He wandered through the offices, and when anyone asked him who he was, he would say 'I'm Fat Charlie Nancy', and he'd say on in his god-voice, which would make whatever he said practically true.

He found the tea-room, and made himself several cups of tea. Then he carried them back to Fat Charlie's desk, and arranged them around it in an artistic fashion. He started to play with the computer network. It asked him for a password. 'I'm Fat Charlie Nancy,' he told the computer, but there was still places it didn't want him to go, so he said, 'I'm Grahame Coats,' and it opened to him like a flower.

He looked at things in the computer until he got bored.

He dealt with the contents of Fat Charlie's in-basket. He dealt with Fat Charlie's pending basket.

It occurred to him that Fat Charlie would be waking up around now, so he called him at home, in order to reassure him; he just felt that he was making a little headway when Grahame Coats put his head round the door, ran his fingers across his sloat-like lips, and beckoned.

'Gotta go," Spider said to his brother. 'The big boss needs to talk to me.' He put down the phone.

'Making private phone calls on company time, Nancy,' stated Grahame Coats.

'Abso-friggin'-lutely,' agreed Spider.

'And was that myself you were referring to as "the big boss"?' asked Grahame Coats. They walked to the end of the hallway, and into his office-

'You're the biggest,' said Spider. 'And the bossest.'

Grahame Coats looked puzzled; he suspected he was being made fun of, but he was not certain, and this disturbed him.

'Well, sit ye down, sit ye down,' he said.

Spider sat him down.

It was Grahame Coats's custom to keep the turnover of staff at the Grahame Coats Agency fairly constant. Some people came and went. Others came, and remained until just before their jobs would begin to carry some kind of employment protection. Fat Charlie had been there longer than anyone: one year and eleven months. One month to go before redundancy payments or industrial tribunals could become a part of his life.

There was a speech that Grahame Coats gave, before he fired someone. He was very proud of his speech.

'Into each life,' he began, 'a little rain must fall. There's no cloud without a silver lining.'

'It's an ill wind,' offered Spider, 'that blows no one good.'

'Ah. Yes. Yes indeed, Well. As we pass through this vale of tears, we must pause to reflect that-'

'The first cut,' said Spider, 'is the deepest.'

'What? Oh.' Grahame Coats scrambled to remember what came next. 'Happiness,' he pronounced, 'is like a butterfly.'

'Or a bluebird,' agreed Spider.

'Quite. If I may finish?'

'Of course. Be my guest,' said Spider, cheerfully.

'And the happiness of every soul at the Grahame Coats Agency is as important to me as my own.'

'I cannot tell you,' said Spider, 'how happy that made me.'

'Yes,' said Grahame Coats.

'Well, I better get back to work,' said Spider. 'It's been a blast, though. Next time you want to share some more, just call me. You know where I am.'

'Happiness,' said Grahame Coats. His voice was taking on a faintly strangulated quality. 'And what I wonder, Nancy, Charles, is this - are you happy here? And do you not agree that you might be rather happier elsewhere?'

'That's not what I wonder,' said Spider. 'You know what I wonder?'

Grahame Coats said nothing. It had never gone like this before. Normally, at this point, their faces fell, and they went into shock. Sometimes they cried. Grahame Coats had never minded when they cried.

'What I wonder,' said Spider, 'is what the accounts in the Cayman Islands are for. You know, because it almost sort of looks like money that should go to our client accounts sometimes just goes into the Cayman Islands accounts instead. And it seems a funny sort of way to organise the finances, for the money coming in to rest in those accounts. I've never seen anything like it before. I was hoping you could explain it to me.'

Grahame Coats had gone off-white - one of those colours that turn up in paint catalogues with names like Parchment or Magnolia. He said, 'How did you get access to those accounts?'

'Computers,' said Spider. 'Do they drive you as nuts as they drive me? What can you do?'

Grahame Coats thought for several long moments. He had always liked to imagine that his finantial affairs were so deeply tangled that, even if the Fraud Squad were ever able to conclude that finantial crimes had been commited, they would find it extreamly difficult to explain to a jury exactly what kind of crimes they were.

'There's nothing illegal about having offshore accounts,' he said, as carelessly as possible.

'Illegal?' said Spider. 'I should hope not. I mean, if I saw anything illegal, I should have to report it to the appropriate authorities.'

terça-feira, 5 de novembro de 2013

'Neverwhere' - Neil Gaiman

"What," asked Mr Croup, "do you want?"

"What", asked the Marquis de Carabas, a little more rethorically, "does anyone want?"

"Dead things," suggested Mr Vandemar. "Extra teeth."

"I thought perhaps we coul make a deal," said the Marquis.

Mr Croup began to laugh. It sounded like a piece of blackboard being dragged over the nails of a wall of severed fingers. "Oh, Messire Marquis. I think I can confidently state, with no risk of contradiction from any parties here present, that you have taken leave of whatever senses you are reputed to have had. You are," he confided, "if you will permit the vulgarism, completely off your head."

"Say the word," said Mr Vandemar, who was now standing behind the Marquis' chair, "and it'll be off his neck before you can say Jack Ketch."

The Marquis breathed heavily on his fingernails, and polished them on the lapel of his coat. "I have always felt," he said, "that violence was the last refuge of the incompetent, and empty threats the final sanctuary of the terminally inept."

Mr. Croup glared. "What are you doing here?" he hissed.

The Marquis de Carabas stretched, like a big cat: a lynx, perhaps, or a huge black panther; and at the end of the stretch he was standing up, with his hands thrust deep in the pockets of his magnificent coat.

"You are," he said, idly and conversationally, "I understand, Mister Croup, a collector of Tang dynasty figurines."

"How did you know that?"

"People tell me things. I'm approachable." The marquis's smile was pure, untroubled, guileless: the smile of a man selling you a used Bible.

"Even if I were . . . " began Mr. Croup.

"If you were," said the Marquis de Carabas, "you might be interested in this." He took one hand out of his pocket and displayed it to Mr. Croup. Until earlier that evening it had sat in a glass case in the vaults of one of London's leading merchant banks. It was listed in certain catalogs as The Spirit of Autumn (Grave Figure). It was roughly eight inches high: a piece of glazed pottery that had been shaped and painted and fired while Europe was in the Dark Ages, six hundred years before Columbus's first voyage.

Mr. Croup hissed, involuntarily, and reached for it. The marquis pulled it out of reach, cradled it to his chest. "No no," said the Marquis. "It's not as simple as that."

"No?" asked Mr. Croup. "But what's to stop us taking it, and leaving pieces of you all over the Underside? We've never dismembered a Marquis before."

"Have," said Mr. Vandemar. "In York. In the fourteenth century. In the rain."

"He wasn't a marquis," said Mr. Croup. "He was the earl of Exeter."

"And marquis of Westmorland." Mr. Vandemar looked rather pleased with himself.

Mr. Croup sniffed. "What's to stop us hacking you into as many pieces as we hacked the marquis of Westmorland?" he asked.

De Carabas took his other hand out of his pocket. It held a small hammer. He tossed the hammer in the air and caught it by the handle, ending with the hammer poised over the china figurine.

"Oh, please," he said. "No more silly threats. I think I'd feel better if you were both standing back over there."

Mr. Vandemar shot a look at Mr. Croup, who nodded, almost imperceptibly. There was a tremble in the air, and Mr. Vandemar was standing beside Mr. Croup, who smiled like a skull. "I have indeed been known to purchase the occasional Tang piece," he admitted. "Is that for sale?"

"We don't go in so much for buying and selling here in the Underside, Mister Croup. Barter. Exchange. That's what we look for. But yes, indeed, this desirable little piece is certainly up for grabs."

Mr. Croup pursed his lips. He folded his arms. He unfolded them. He ran one hand through his greasy hair. Then, "Name your price," said Mr. Croup.

The marquis let himself breathe a deep, relieved, and almost audible sigh. It was possible that he was going to be able to pull this whole grandiose ruse off, after all. "First, three answers to three questions," he said.

Croup nodded. "Each way. We get three answers too."

"Fair enough," said the marquis. "Secondly, I get safe conduct out of here. And you agree to give me at least an hour's head start."

Croup nodded violently. "Agreed. Ask your first question." His gaze was fixed on the statue.

"First question. Who are you working for?"

"Oh, that's an easy one," said Mr. Croup. "That's a simple answer. We are working for our employer, who wishes to remain nameless."

"Hmph. Why did you kill Door's family?"

"Orders from our employer," said Mr. Croup, his smile becoming more foxy by the moment.

"Why didn't you kill Door, when you had a chance?"

Before Mr. Croup could answer, Mr. Vandemar said, "Got to keep her alive. She's the only one that can open the door."

Mr. Croup glared up at his associate. "That's it," he said. "Tell him everything, why don't you?"

"I wanted a turn," muttered Mr. Vandemar.

"Right," said Mr. Croup. "So you've got three answers, for all the good that will do you. My first question: why are you protecting her?"

"Her father saved my life," said the marquis, honestly. "I never paid off my debt to him. I prefer debts to be in my favor."

"I've got a question," said Mr. Vandemar.

"As have I, Mr. Vandemar. The Upworlder, Richard Mayhew. Why is he traveling with her? Why does she permit it?"

"Sentimentality on her part," said the marquis de Carabas. He wondered, as he said it, if that was the whole truth. He had begun to wonder whether there might, perhaps, be more to the upworlder than met the eye.

"Now me," said Mr. Vandemar. "What number am I thinking of?"

"I beg your pardon?"

"What number am I thinking of?" repeated Mr. Vandemar. "It's between one and a lot," he added, helpfully.

"Seven," said the marquis. Mr. Vandemar nodded, impressed. Mr. Croup began, "Where is the--" but the marquis shook his head. "Uh-uh," he said. "Now we're getting greedy."

There was a moment of utter silence, in that dank cellar. Then once more water dripped, and maggots rustled; and the marquis said, "An hour's head start, remember."

"Of course," said Mr. Croup. The marquis de Carabas tossed the figurine to Mr. Croup, who caught it eagerly, like an addict catching a plastic baggie filled with white powder of dubious legality. And then, without a backward glance, the marquis left the cellar.

'Pride and Prejudice' ('Orgulho e Preconceito) - Jane Austen

'While settling this point, she was suddenly roused by the sound of the door-bell, and her spirits were a little fluttered by the idea of its being Colonel Fitzwilliam himself, who had once before called late in the evening, and might now come to inquire particularly after her. But this idea was soon banished, and her spirits were very differently affected, when, to her utter amazement, she saw Mr. Darcy walk into the room. In an hurried manner he immediately began an inquiry after her health, imputing his visit to a wish of hearing that she was better. She answered him with cold civility. He sat down for a few moments, and then getting up, walked about the room. Elizabeth was surprised, but said not a word. After a silence of several minutes, he came towards her in an agitated manner, and thus began-

"In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you."

Elizabeth's astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, coloured, doubted, and was silent. This he considered encouragement; and the avowal of all he felt, and had long felt for her, immediately followed. He spoke well; but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed, and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride. His sense of inferiority - of its being a degradation - of the family obstacles which judgment had always oppose to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

In spit of her deeply-rooted dislike, she could not be insensible to the complement of such a man's affection, and though her intentions did not vary, for an instant, she was at first sorry for the pain he was to receive; till, roused to resentment by his subsequent language, she lost all compassion in anger. She tried, however, to compose herself to answer him with patience, when he should have done. He concluded with representing to her strength of that attachment which, in spite of all his endeavours, he had found impossible to conquer; and with expressing his hope that it would now be rewarded by her acceptance of his hand. As he said this, she could easily see that he had no doubt of a favourable answer. He spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed real security. Such a circumstance could only exasperate farther, and, when he ceased, the colour rose into her cheeks, and she said-

"In such cases as this, it is, I believe the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the sentiments avowed, however unequally they may be returned. It is natural that obligation should be felt, and if I could feel gratitude, I would now thank you. But I cannot - I have never desired your good opinion, and you have certainly bestowed it most unwillingly. I am sorry to have occasioned pain to anyone. It has been most unconsciously done, however, and I hope will be of short duration. The feelings which you tell me, have long prevented the acknowledgement of your regard, can have little difficulty in overcoming it after this explanation."

Mr. Darcy, who was leaning against the mantelpiece with his eyes fixed on her face, seemed to catch her words with no less resentment than surprise. His complexion became pale with anger, and the disturbance of his mind was visible to every feature. He was struggling for the appearance of composure, and would not open his lips till he believed himself to have attained it. The pause was to Elizabeth's feelings dreadful. At length, in a voice of forced calmness, he said-

"And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance."

"I might as well inquire," replied she, "why with so evidence a design of offending and insulting me, you chose to tell me that you liked me against your will, against your reason, and even against you character? Was not this some excuse for incivility, if I was uncivil? But I have other provocations. You know I have. Had not my own feelings decided against you - had they been indifferent, or had they even been favourable, do you think that any consideration would tempt me to accept the man who has been the means of ruining, perhaps for ever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?"

As she pronounced the words, Mr. Darcy changed colour; but the emotion was short, and he listened without attempting to interrupt her while she continued-

"I have every reason in the world to think ill of you. No motive can excuse the unjust and ungenerous part you acted there. You dare not, you cannot deny that you have been the principal, if not the only means of dividing them from each other . of exposing one to the censure of the world for caprice and instability, the other to its derision for disappointed hopes, and involving them both in misery of the acutest kind."

She paused and saw with no slight indignation that he was listening with an air which proved him wholly unmoved by any feeling of remorse. He even looked at her with a smile of affected incredulity.

"Can you deny that you have done it?" she repeated.

With assumed tranquility he then replied, "I have no wish of denying that I did everything in my power to separate my friend from your sister, or that I rejoice in my success. Towards him I have been kinder than towards myself."

Elizabeth disdained the appearance of noticing this civil reflection, but its meaning did not escape, nor was it likely to conciliate her.

"But it is not merely this affair", she continued, "on which my dislike is founded. Long before it had taken place my opinion of you was decided. Your character was unfolded in the recital which I received many months ago from Mr. Wickham. On this subject, what can you have to say? In what imaginary act of friendship can you here defend yourself? or under what misrepresentation can you here impose upon others?

"You take an eager intent in that gentleman's concerns," said Darcy, in a less tranquil tone, and with a heightened colour.

"Who that knows what his misfortunes have been, can help feeling an interest in him?"

"His misfortunes!" repeated Darcy contemptuously; "yes, his misfortunes have been great indeed."

"And of your infliction", cried Elizabeth with energy. "You have reduced him to his present state of poverty - comparative poverty. You have withheld the advantages which you must know to have been designed for him. You have deprived the best years of his life of that independence which was no less his due than his desert. You have done all this! and yet you can treat the mention of his misfortunes with contempt and ridicule."

"And this," cried Darcy, as he walked with quick steps across the room, "is your opinion of me! This is the estimation in which you hold me! I thnk you for explaining it so fully. My faults, according to this calculation, are heavy indeed! But perhaps," added he, stopping in his walk, and turning towards her, "these offences might have been overlooked, had not your pride been hurt by my honest confession of the scruples that had long prevented my forming any serious design. These bitter accusations might have been suppressed, had I, with greater policy, concealed my struggles, and flattered you into the belief of my being impelled by unqualified, unalloyed inclinations; by reason, by reflection, by everything. But disguise of every sort is my abhorence. Nor am I ashamed of the feelings I related. They were natural and just. Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your conections? - to congratulate myself on the hope of relations, whose condition in life is so decidely beneath my own?"

Elizabeth felt herself growing more angry every moment; yet she tried to the utmost to speak with composure when she said-

"You are mistaken, Mr. Darcy, if you suppose that the mode of your declaration affected me in any other way, than as it spared me the concern which I might have felt in refusing you, had you behaved in a more gentlemanlike manner."

She saw him start at this, but he said nothing, and she continued-

"You could not have made me the offer of your hand in any possible way that would have tempted me to accept it."

Again his astonishment was obvious; and he looked at her with an expression of mingled incredulity and mortification. She went on-

"From the very beginning - from the first moment, I may almost say - of my acquaintance with you, your manners, impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish desdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form the groundwork of disapprobation on which succeeding events have built so immovable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry."

"You have said quite enough, madam. I perfectly comprehend your feelings and have now only to be ashamed of what my own have been. Forgive me for having taken up so much of your time, and accept my best wishes for your health and happiness."

And with these words he hastily left the room, and Elizabeth heard him the next moment open the front door and quit the house.'

Subscrever:

Comentários (Atom)